In this presentation from the 2018 Typefi User Conference, Simon De Nicola, Head of the Publication Production Department at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), shares the challenges and successes of implementing accessibility as part of ITU’s everyday publishing practices.

Transcript

SIMON DE NICOLA: Good morning, my name is Simon De Nicola and I’m Head of Publication Production Service at ITU in Geneva. Very pleased to be here today to present the work we’ve done so far.

About the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

In 1858, the first transatlantic telegraph cable was laid, but there was a problem. When the line crossed national borders, messages had to be stopped and made accessible—basically translated into the national system, the particular system of the next jurisdiction.

So, 20 European states decided to meet in Paris. It was the first International Telegraph Conference to discuss how they could communicate better. This has led to the signature of the Convention and the creation of the International Telegraph Union in 1865, that’s the birth of our organisation.

ITU took its present name in 1934. In 1947 it became a specialised agency of the United Nations and moved to Geneva. Today we are the United Nations specialised agency for information and communication technologies called ICTs.

We have three main areas of activities which we call sectors, working through conferences and meetings.

The first one, ITU-R, Radiocommunication, coordinates a vast range of radio communication services, like satellite and wireless communications, broadband services, as well as the international management of the radio frequency spectrum and the assignation of orbital slots for satellites.

This sector also coordinates some work on mobile broadband communication and broadcasting technology such as Ultra HD TV and 3D TV.

The Standardization, ITU-T, develops technical standards that ensure networks and technology seamlessly interconnect. Without our standards you couldn’t make a phone call or surf the internet.

This sector works on internet access transport protocol, voice and video compression, home networking, et cetera, et cetera. One of our most popular standards is the Emmy-award-winning H.264 which is used for video compression.

In any typical year we produce revised or up to 150 standards covering everything from network functionality to next-generation services.

The last sector is ITU-D, the Development, which strives to improve access to ICTs to underserved communities worldwide, and helps connecting emerging markets.

This sector champions a number of global initiatives like Bridge the Digital Divide, Broadband For All, or Connect a School, Connect a Community. It also publishes the industry’s most comprehensive and reliable ICT statistics.

ITU Publication Production Service

Okay, so for our service we are basically a 28 strong team. We have 15 different nationalities. We provide very comprehensive services to our internal clients, the three sectors.

We do administration, project management, graphics, page layout formatting, and multimedia development.

The editorial aspect is usually managed by our clients. Translation is done within our division as well. By the way, we publish in six languages—three European, and Russian, Chinese and Arabic, which is always a challenge as far as publication is concerned.

We have shifted from paper-based publications to electronic versions about 15 years ago. We’re producing systematically in PDF version in addition to paper version, and we distribute everything via our e-library.

We produce several hundred publications a year. I think in 2017 we did 217 new publications. The trends we’ve noticed is that paper is down, e-formats are up.

Digital formats accounted for 72% of our sales, and paper format only 26%, and obviously we distribute our electronic formats through various media—CD-ROM, DVD, USB keys and obviously online as well.

Why accessibility?

Okay, why? Why accessibility?

I think Chandi actually raised a few interesting points earlier, but basically it’s because persons with disabilities are like everyone else.

Technology is central to their lives, and obviously when a system is not designed following accessibility standards and guidelines, individuals with physical, sensorial, or cognitive impairments will become disabled—disabled by technology and excluded from essential services available to other citizens.

I was also personally interested by the project because I have a deaf colleague, which has been working with us for more than a decade. Communication is fine with her. Sometimes challenging— she lip reads, which means she usually understands my words but I’ve noticed it was actually quite different to what I meant. So I used, in this case, ICTs or the written form in order to clarify.

However, when she has to communicate particularly with the administration, the communication is becoming a nightmare.

The legal framework—because we are a UN agency we had to abide by several rules. So, we had to actually move to accessible publishing because of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2006 and signed by 159 countries.

The interesting thing with that convention is that it switched to a human rights model of disability, which typically expressed a moral and political commitment that country, state and organisations should take with regard to persons with disabilities.

In earlier models, disabilities was described with reference to the medical conditions that were seen to rise from, and the focus of disability management was on professionals curing or treating the condition.

Then followed the social model, which revolutionised the understanding of disability by arguing that it was not mainly caused by impairments but by the way society was organised and responded to people with disabilities.

ITU adopted Resolution 175 during our Plenipotentiary Conference in 2010. This resolution invited us to promote access for persons with disabilities to new ICT systems including the internet, of course.

This has finally led to our accessibility policy for persons with disabilities, which was adopted with our council in 2013.

The impact of accessibility is huge, and affects directly the lives of millions of people. I have slightly different figures than you, Chandi but I think our sources are very similar.

WHO estimates that there are 1 billion people with varying degrees of physical, sensory or cognitive disabilities in the world which represents, according to this new report, 15% of the world’s population, 80% of them being obviously in developing countries.

So, the UN decided that accessibility to ICT would be defined as a fundamental right equivalent to accessibility to building and transportation, both from a digital accessibility and assistive technology standpoint, which is very important for publication.

After all, ICT does provide opportunities and benefits for all, and overcomes exclusion on the basis of gender or disability.

The accessible publications project

So, the implication for us became obvious. As we are involved in technical standards for the industry, recommendations for regulators and governments, statistic and infrastructure plans for developing countries, our text had to become accessible.

But there was no brief, no input. We were a bit lost on how to start this project. For our clients it was business as usual and one urgent project after the other.

So, we started looking inwards and realised that our workflow was problematic. Traditionally the main method we used was Word, PDF, even though paper production was down and we hardly printed.

We knew that with this format we could not really deliver on new platforms or reach new media. The accessibility was minimal, which was limited to text. The document structure was left to the author and was very inconsistent. The output formats were limited to non-reflowable text and non-scalable files.

Adding the accessibility later at the end of the publication process was feasible. We did it for several reports but required a lot of time and resources. It was also unrealistic with urgent publication and given the volume of work that we are producing.

So, we realised that if we wanted to address properly user accessibility needs, we had to include it directly in the design process of a new workflow.

As accessibility is a very broad topic for publication, we decided to limit the focus on a wide range of visual impairments and obviously in six languages.

We decided to integrate compatibility with mobile systems to take advantage of assistive technologies which were built into new equipment. Mobile phone technology can combine audio, text and voice, and is a fantastic enabler for persons with disabilities.

We also definitely wanted to provide more visibility to our publications and to adapt them to a rapidly evolving publishing landscape where fixed formats were being replaced gradually by formats which adapted to new ways of consuming, and where the structure of the content was also evolving.

Chapters were becoming shorter and more digestible. Cross referencing was a must, and the content was becoming easier to use thanks to the replacement of stringent copyright with Creative Commons licensing. This is actually work that we’re still doing and this is still ongoing for us.

So, the brief became “accessible to all”, reaching our readers on media that they use on a daily basis. We decided that our publication had to become downloadable on PC or Mac, on smartphone or tablets, and supplied in multiple formats that users were expecting to find.

But we also needed old-style paper copies because typically the author says, “Yes this whole new system is fantastic. We really want all this, we want accessibility, but we still need one or two printed copies just to give away or to take home.”

So, to maximise visibility, we decided to increase the distribution channels and to generate several additional formats, all, of course, including metadata. We wanted accessibility with usability and availability, both ease-of-use and success of use.

Project timeline

This was the project timeline. We started looking for a product which would deliver all this. The first time I think we met with the Typefi team, and Chandi and his team of experts was in 2012.

At that time I was actually working on several accessible reports which were tweaked on PDF in order to make them really accessible. Although it wasn’t really real accessibility—I think it was just patching, but at the time that’s all we could do.

2013 was a year off. I think Guy and Chandi will remember that I had a little accident and I was away for a while.

And then we started again consultations. We consulted with many experts—with G3ict, Microsoft, DAISY, of course, and the Institute for the Blind.

We focused the production on several reports like Making Television Accessible, but that was again a long and tedious work to work on the PDF version.

The UN being the UN and administration being administration, we launched finally a call for bids. Eventually the contract was signed and the real work with Typefi eventually started in 2014.

We had to change our production environment without stopping the flow of work, which was a little bit of a nightmare. Also, I think change management was difficult.

You remember I said earlier that we have 15 different nationalities in our team. So convincing everyone that accessibility was a must was, and still is, actually ongoing.

The most difficult part I find is still convincing the authors or the editors to ‘think accessibility’ when they actually write the text, because they’re so focused on the subject that they forget that this has to be simplified sometime, re-explained for when you have graphics and when you have figures.

And again, everybody is always in a rush and every single job ends up becoming urgent.

But eventually everyone understood the benefits of the product.

So 2015 was focusing basically on the production and on improving templates, and we really standardised the use of the system in 2016.

Project deliverables

Typefi did the installation of the software on our servers. The contract included maintenance and troubleshooting, off-site technical support, and obviously several training sessions for designers and operators.

Guy, which is always precious to us, created the original templates in English in three output formats. We requested accessible and printable PDF, again because the paper format is still important, EPUB format, which is obviously a recognised XML standard for text-based and digital reflowable books.

And originally we requested DAISY, because again we wanted to go quite far in the accessibility and the further step was to actually produce some books in Braille. But then after some internal discussion and discussion with the experts here in Typefi we switched this to a Kindle format.

So, in fact, now we’re producing MOBI as well, and this was basically with a view to actually broaden again our range of product and our platform of distributions.

On our side, we took charge of the adaptation and creation of the three templates in five languages. That was done by our internal graphic designers. We created additional templates—again, that was the graphic designers in collaboration with the authors.

We created some guidelines for editors and authors, and a new workflow where the author provides the manuscript, the operator formats and checks for accessibility compatibility before sending it back, and so we do several rounds of round-trip editing until we actually reach the final format. It usually takes several versions before the publication is finalised.

And then we obviously took charge, as well, of accessible publishing specificities training with our operators internally.

Where are we today?

We have launched on the third of December 2017, which was in fact the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, we actually launched our new website.

We have on this website 60-plus titles, all downloadable from the bookshop. A lot of them are available in six languages. I will just show you a little bit later a quick demo of those.

We’re still working hard at convincing the editors in making our text more accessible, but because quite often we have a lot of complicated text and very technical text, they’re quite reluctant to do so. But we’ve noticed that the mentality is slowly changing and people are slowly adapting.

So today, basically all of these publications are what I call accessible, for us in any case. They’re not, as you said, maybe they’re not triple A because again they’re complicated text. There’s still a lot of tables which the authors refuse to change, but to me they are machine readable, which is essential.

The text and colour contrast are adjustable, they contain navigational aids, they also have alternative text descriptions for non-textual elements. The structure has been rearranged, and another very important key element is ensuring that the content is separated from the final presentation to ensure the operability across different devices and systems.

Examples of accessible publications

Note: Links to the documents discussed here are provided at the bottom of this section.

So I think I will just switch to…

This is our website containing basically all these publications in accessible formats. I invite you to go and have a look at those.

This is the fairly recent production—there’s all sorts of reports, all sorts of handbooks, all sorts of toolkits as well, and again several are in multiple languages. This is all production from 2016 to today.

This is what a report looks like in its PDF form. The layout is not super sophisticated but I think it’s quite clean and readable. We have of course again a lot of text, a lot of graphics.

This is another sample. We are actually using several macros to change the colour of the main text on the PDF format, and that’s according to the categorisation that we’ve adopted internally.

And this is the equivalent again in Arabic.

So all these are basically using very similar templates and all these are actually produced in PDF format, obviously accessible PDFs, in e-books and in Kindle format.

This is the EPUB version. I think that’s where really accessibility shows all its power. Basically, the same book that you saw just a little bit earlier is now present on e-book. It’s downloadable, of course, from the website.

SCREEN READER: The second long term trend is the growth in broadband, defined in this report as services with speeds of 256 kbits/s.

SIMON: And it’s fully machine readable. I think that’s where really accessibility shows you all its power.

[Video: Simon switches to a version of the EPUB written in Chinese characters.]

[Screen reader reads text out loud in Chinese.]

For those who understand Chinese.

This was presented into several of our conferences and was highly appreciated by our delegates who really insisted that our work should become accessible.

So, I’m proud to say that they are now, even though they’re not fully accessible. Thank you.

Links to examples

- ITU Accessible Publications website

- Measuring the Information Society Report 2017 (PDF)

- Digital Skills Toolkit (page includes download links for PDF, EPUB, and Kindle)

Q&A

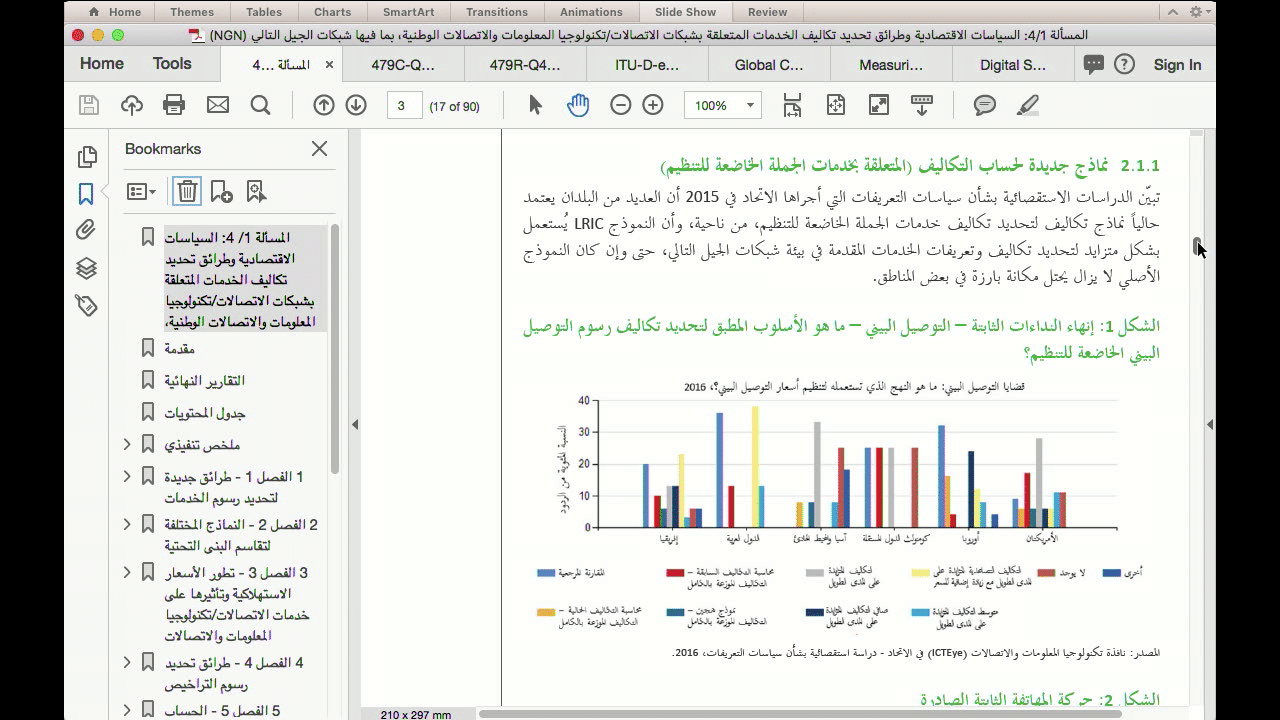

GUEST 1: Hello, I’ve got a couple of questions actually. I thought firstly when you were looking at that bar chart there, I was wondering what actually in terms of accessibility has been attached to it. Is it actually listing all of the data? You know, about you having to describe what is a visual chart. That’s the first question.

SIMON: Sure, that’s a very good question and that’s a cause for a lot of discussion with the authors and the translators. I think it’s completely variable.

We have about 100 different authors contributing to publications. Some provide full descriptions, visual descriptions, of what is represented on the graphs and that I consider as triple A fully accessible.

Others just repeat basically the title of the graph, which really is very poor in terms of accessibility, and by default, when nothing is given to us, that’s what we do, basically. We just repeat simply the text of the chart, rather than go directly to detail.

Unfortunately we do not have editing capacities in-house. As I mentioned right at the beginning, in our operations we’re really focusing on the formatting aspect and no more on the content aspect because that was outsourced many years ago.

So it’s our authors, if you want, which are responsible for the content and very often it’s consultants.

I think we’re moving forward slowly because in the new contracts, in the new consultant contracts we have built in a clause for accessibility and for providing alternative text to images, to photographs and figures. So this is slowly moving on and getting more and more accessible.

GUEST 1: Thank you. Me again, okay, second question. You said you had some difficulty convincing editors to make things more accessible. Could you give a little example of what the reluctance was and then how the end outcome was?

SIMON: We have one flagship report on statistics, and trying to convince an economist to make an accessible chart is almost impossible.

I think that for them the data is essential, and when you ask them, you try to explain to them what accessibility is, they just respond, “Look you know all the data is there. You just have to read it.”

So, I think that there is still a big, big reluctance of changing again the mentality, changing the way they think, and adapting to ways that would be better understood by other people.

However, I think that there’s—maybe if I can go back onto our website, there is a tool which is used by these, this is actually figures which are taken again from the same report, from Measuring the Information Society Report, which is full of statistics.

Here, they’re using different ways of actually presenting the information, which is really much more interactive and can be—is—much more accessible.

So even though we moved away from the publication itself, the data from the publication is then being used to actually build an interactive website where all the data is contained. I think that’s a good example of how accessibility can move from one media to the other.

CHANDI PERERA: Do you have any statistics? I know it’s early days, but how many people are actually using the accessible versions? Or the non-PDF versions?

SIMON: Thank you for asking that question, but I have been trying to get statistics for the past three weeks and unfortunately, no, I don’t.

We’ve been doing a lot of work since 2015 reaching out, and we have now partnerships with the OECD and the UN publications. So it’s really early days. They have a lot of additional formats, EPUBs and Kindle, but unfortunately I don’t have any kind of a solid statistic yet.

I think I tend to agree with you—PDF is up again, even though I find it quite frustrating because I think EPUB is such a wonderful format that allows us to access all these new media.

I still think that yes, I think PDF is still very strong and is still the favoured format, so.

GUEST 2: You mentioned that you gave authors and editors some guidelines. Did they contain guidelines for developing good alt text or do you know if there are some available?

SIMON: Yes, we basically rewrote guidelines based on the guidelines we had read before. Again, the OECD has actually very, very good guidelines on accessible text.

I think that there’s so many versions that exist now, that you can find some pretty good examples everywhere, but again I think the difficulty is just changing the mentality, making people think accessibility rather than just writing the text.

But the technical guidelines are there. I could make them available should you wish so.

GUEST 2: Got another one as well. You mentioned briefly that you’re moving to your Creative Commons licence. Is there any particular reason why?

SIMON: Yes, because copyright is very restrictive. Up to now or to recently we’ve been using the standard copyright which says that if you want to use our content you have to ask us. So that’s not very accessible is it?

The Creative Commons licensing have different levels of copyright, which can be as protective as the standard copyright but can also be very permissive, and I believe that for content which is given for free, why should people ask permission? It doesn’t really make sense and doesn’t really make your content accessible.

So, to me, it’s a full part of accessibility as well.

Simon De Nicola

Head, Publication Production Department | International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

Passionate about new technologies and the constant evolutions in the publishing industry, Simon led the transition of his unit from paper-based book production to a service creating accessible publications in the six United Nations working languages.

Prior to joining ITU, Simon worked in London as an independent and consulting graphic designer before being recruited by EBRD to work on their Annual Reports and Intranet system. Previously he graduated in 1987 from Toulouse School of Arts with an M.A. in Industrial and Graphic Design.