In this panel presentation from the 2021 Typefi Standards Symposium, Anja Bielfeld, IT Business Analyst at the IEC, and Kylie Rodier, Digital Publishing Manager at ISO Central Secretariat, discuss new initiatives and activities currently underway at both organisations.

Topics include XML-based authoring, collaboration on a shared XML schema, and machine-readability in the context of standards.

“All of these initiatives open up new possibilities for standards development organisations, and also for supporting our users in the consultation of our standards.”

Transcript | Q&A session | Presenters

Transcript

| 00:00 | A brief history of publishing at ISO and IEC |

| 01:24 | NISO STS collaboration |

| 02:09 | Online Standards Development (OSD) Program |

| 04:11 | IEC standards in database format |

| 06:12 | Digitalisation and ISO SMART (machine-readable standards) |

| 09:58 | Opportunities for new products and services |

| 11:54 | Conclusion |

A brief history of publishing at ISO & IEC (00:00)

KYLIE: We’re here today to talk about what’s next in standards and standards publishing.

To begin, I’d like to give a very brief historical context of publishing at ISO and IEC. In 1906, IEC was founded and in 1947 ISO was founded. Both organisations started publishing on paper, obviously.

In the 1980s with the advent of email, internet, SGML, business practice started entering the digital age. The 1990s saw the invention of the PDF and of XML, and in the 1990s and 2000s, PDFs were integrated into IEC and ISO’s tool chains as part of publishing.

In 2008, ISO/CS was mandated to provide XML versions of standards, and IEC started doing this in 2015.

In 2018, IEC formed a Strategic Group on Digital Transformation, otherwise known as SG 12, and in 2019, ISO had a Strategic Advisory Group on Machine-Readable Standards otherwise known as SAG MRS.

And in 2020 both organisations are working on the Online Standards Development program. And we’ll go into more detail on that later.

NISO STS collaboration (01:24)

Both organisations have been collaboratively working on using the same XML schema for the XML provided by both organisations. IEC and ISO are now using NISO STS, as are CEN-CENELEC and various members.

NISO STS is a document-centric schema that allows for semantic enrichment, and we hope that this will prove useful as we develop standards formats and the granularity of our standards in the future.

ISO and IEC published the NISO STS XML Coding Guidelines earlier this year, and NISO STS is the schema used in the Online Standards Development program.

The Online Standards Development (OSD) Program (02:09)

ANJA: The Online Standards Development program is another very important collaboration between IEC and ISO, which will eventually include participation from tens of thousands of experts worldwide, who today produce standards for IEC, for ISO, and will in the future be using an Online Standards Development tool.

At the heart of which is the Editor that Fonto has come up with, and Fonto is also represented in this symposium, so they will talk more about their product at a later point.

The Fonto Editor is an XML-based tool that we are now integrating into our standards development process for drafting standards. The great thing about it is that we can completely configure it to our own needs, which means we can implement the rules of IEC and of ISO standards development into the tool, and thereby supporting experts in the whole workflow of drafting a standard.

There are lots of pain points that we’re addressing with this. I can’t go into detail on them right now because that would just take too long, but we’re really trying to facilitate the work of our experts, who give their free time to work on standards that we then publish.

And we’re also trying to improve the situation for our members, the national committees, in that we offer a way of facilitated commenting that is required at the voting stages. So for each standard that is published, we have various stages where the standard needs to be voted on and where comments need to be made by our national representatives, and that’s something we want to facilitate by offering an online platform of doing that.

IEC standards in database format (04:11)

So generally, I think we can say that we’re trying to move to the future of standards development by making contents more granular, more modular.

Another approach in this context was undertaken by IEC about 15 years ago, when we created a web application to allow the online creation and the lifecycle management of structured content, which is basically based on databases.

So, we have a database that contains the content in a very structured modular way, and on top of that, we have a workflow management system that allows us to create content, validate content, in very small pieces.

For example, some standards in database format that we’ve mentioned here are the IEV for terminology, some standards containing graphical symbols, or component data dictionary, which is all a collection of individual pieces of content, such as graphical symbols with their description that can—thanks to the standards in database format application—be managed piece by piece.

So, you can create one graphical symbol, you can send it through its entire lifecycle, you can update it whenever needed, thus always having the most current content online for consultation by the user, allowing easy navigation for users, advanced search functionalities, and all of the advantages that come with more modular and more granular content.

And we currently have a project going on that will allow us put the whole web application on new feet and make it more modern, look at the new technical possibilities we have to create new benefits for standards creators and standards users

Digitalisation and ISO SMART (machine-readable standards) (06:12)

KYLIE: In terms of digitalisation and practice, it’s fairly clear that the world is moving towards more digital-centric business practices, and publishing is no different.

We will see this affect standards development, distribution, and use, and it’s also fairly clear that certain industries are more data-centric than others and require standards in formats that go beyond PDF. Which isn’t to say that PDF would ever die out, but it’s clear that users need more than that.

So, there are new possibilities for products and services in the standards development realm, and the focus seems to be on machine-readability or interoperability.

To that end, the ISO Strategic Advisory Group on Machine-Readable Standards released a report in 2020 to ISO’s governance. This report identified that there is a user and market need for data-centric standards, and that this is particularly relevant for certain technical industries, such as energy and technology and construction and so on.

This concept of machine-readability would affect standards development, right from drafting through to distribution, and the report coined a phrase to describe the concept and formats that would fall under a machine-readable standard: ISO SMART, a Standard that is Machine Applicable, Readable, and Transferable.

The report also discovered, or the group also discovered, that many technical committees are already working on products, methodology, and data sets. And it’s really key that standards development bodies provide these formats as well, as the demand is there.

In terms of machine-readability, we could also say interoperability, transferability—there isn’t really a good global consensus on a definition of machine-readability, but industry-specific ones exist and they all talk about this interaction between data, human, and machine.

In the past, it’s been clear that humans have needed to translate data into a machine-readable format. A machine-readable standard would perhaps take the human out of the equation, allowing the data in the standard to be directly used and processed by a machine.

But that isn’t to say that a machine-readable standard is not also human-readable. The concept takes in a lot of considerations. There are various stakeholders, cybersecurity, lots of potential formats, infrastructure considerations to take into account, distribution, and commercial viability and so on.

What is clear is that in terms of standards development, users and industry practice must guide decision-making. And as multiple organisations and groups are already working on this topic and on products, it’s clear that we, as standards organisations, have to do more work on this as well.

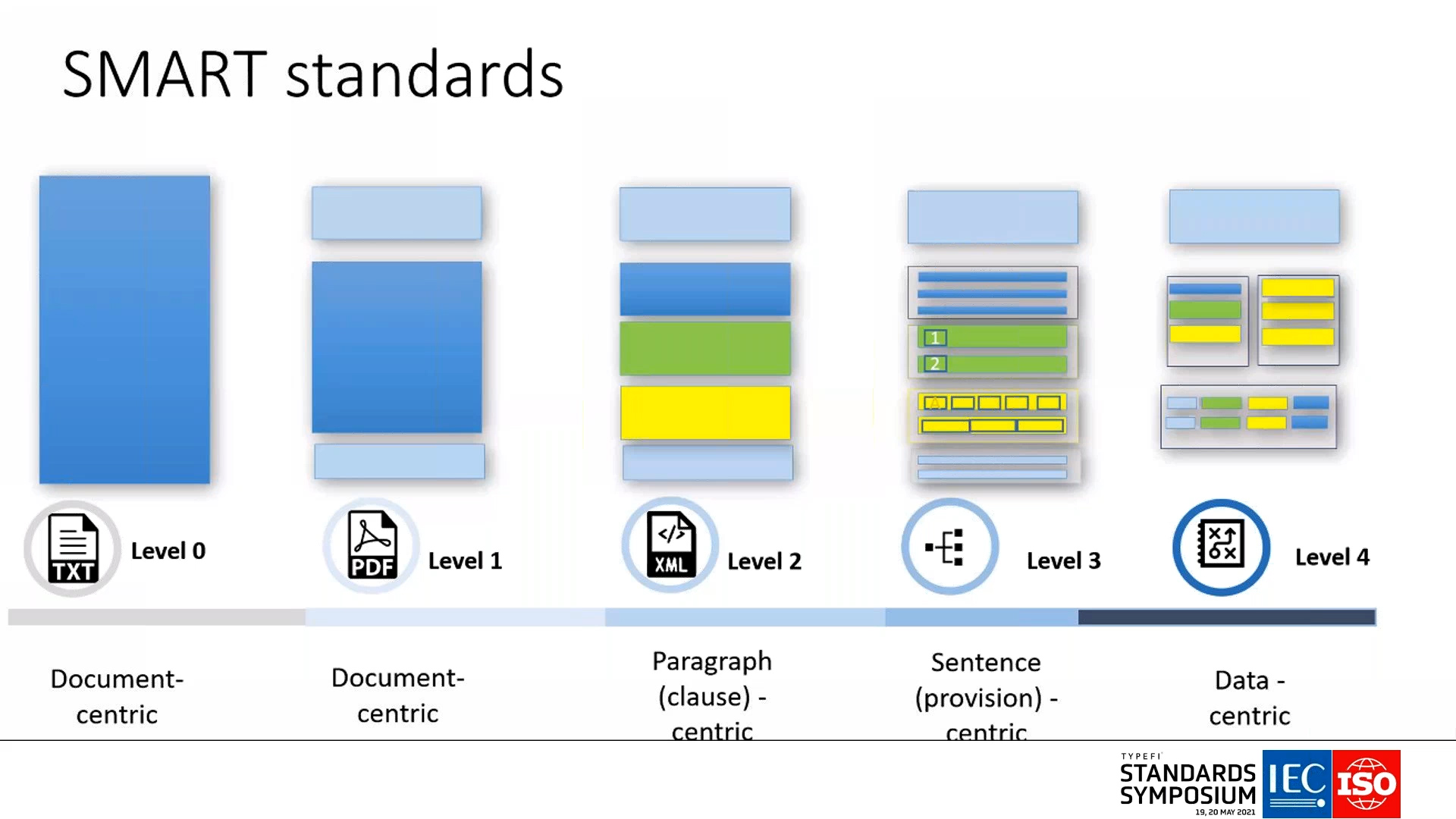

I am sharing a graph here that’s been shared at least at the international level. I like this graph as it shows the concept and in a graphic way about what machine-readability could look like in terms of formats. This is a classification scheme devised of levels, and it shows how machine-readable really requires lots of granularity in terms of data.

Opportunities for new products and services (09:58)

ANJA: All of these initiatives open up new possibilities for standards development organisations, and also for supporting our users in the consultation of our standards.

For us as standards publishers, it will become increasingly easy to create a new output, new formats for our publications; for instance, an increased use of commented redlines, where we show, okay, these are the contents that have changed from the last edition to this one, and these are the reasons why.

We can now track all of the comments that went into the elaboration of a standard and use them at the publication stage.

We can publish to multiple formats, multiple platforms based on the source XML that can be rendered in various different ways. We can also take the XML because of the semantic categories, and also the modular categories of the standards in database format, for instance, and extract different categories for different needs.

For instance, we can extract the terminology in a certain series of standards for use by end users. Or we could imagine showing the relationships between standards because every standard has, in its normative reference section or its bibliography section, dynamic links to the other standards that need to be consulted in order to correctly interpret that standard.

We can graphically illustrate the relationships between standards, and we can make use of all the dynamic cross-references that can now be inserted into our standards and the multiple possibilities of providing contextual information to really make it easy for standards users to interpret the information correctly.

Conclusion (11:54)

So, to conclude, there are important initiatives going on at IEC and ISO. Very importantly, the collaborative authoring, an XML-first approach, which will allow us to create lots of new products and services, and of course the machine-readable standards initiative, SMART standards initiative, where we’ll be able to get to quite a high level of machine-interpretability and exchanging data from our standards with machines that can then just ingest the contents in an automated way.

And finally, we’ll continue to work together and thus—with all the benefits that entails for our common members and, of course, of the synergies that are inherent in working together—we’ll continue to collaborate on the implementation and further harmonisation of the use of our XML schema, NISO STS, between IEC and ISO.

Q&A

Regarding the harmonised systems that you’re implementing across both organisations, what are the challenges you’ve had to solve, and how is your community responding to it?

ANJA: I think the main challenges initially were finding a way work together. Where before there was one organisation and its structures, its governance, its way of working, of leading projects, there were now two that had somehow to harmonise their approaches.

They had to agree on a common approach, which vendor to select along what criteria, and there wasn’t just one boss who could say ‘this is the way we’re going to do it’, everything had to be harmonised between two project teams and two management teams.

Therefore, things may take longer initially, but once we had started to find a way of working together, we’ve started to really see the the synergies and the enhanced possibilities of working together, benefiting from each other’s expertise and possibly different approaches.

Especially for the sake of our common members, who will have to use one system in the future and not two separate systems. I mean, there will be two systems, one at IEC and one at ISO, but they will be similar without differences in the implementation where that’s not absolutely necessary.

KYLIE: It’s really made us look at where our similarities are in terms of data exchange and processes, and where we’re different, and how we can align despite that.

It’s also been interesting to try to anticipate our technical committees’ needs as well in developing the program, in terms of features to provide to them. It’s an ongoing process and it’s very interesting.

ANJA: And, of course, the costs are shared between our two organisations. So, we have one system that we’re implementing and essentially two that can contribute, so we get much more value out of our investment.

In your presentation, you mentioned that the OSD project is addressing a lot of pain points. Can you elaborate on that?

ANJA: We did a series of round tables five, six, seven years ago where we interviewed technical committees and members on what were the biggest pain points for them that they saw in the process of standards development.

Many were related to the fact that with Word, you normally have a standalone document somewhere hidden on someone’s computer, not visible to the other members. Obviously this has changed with Office online, but still there’s many things to know, many controls, many tabs and functionalities in Word that most people don’t use and that are not particularly helpful for standards development.

So, one of the pain points is to find the correct things that you need to do your work. And on the other hand, people became very creative in finding different ways of doing things in Word which led to problems in the production chain later on.

And on the problem of having one Word document on someone’s computer, and another version on another computer, they don’t collaborate. Someone in the end has to merge all the different versions that exist. Sometimes they get the wrong version of one document, and everything is a bit difficult where version control and merging content is concerned.

The biggest problem, however, was really shared between the working groups and between the national committees or the members working with the comments at voting stages. So, during the voting stage, when the national experts input their comments into the IEC or the ISO system, they use a template in addition to the draft that they’re working on. They say, “In line 18 on page 20, change this to that.” That’s not very efficient, it’s not contextual. You always need two documents.

And then in the working group, once they start working on their document, obviously line 18 will be right the first time, but once you insert an additional paragraph, all the line numbers are no use anymore. So there were huge problems there that we’re now trying to solve with the commenting app that we’re putting in place. So they’re the main ones.

Will IEC and ISO collaborate on future projects involving machine-readable standards?

KYLIE: In a way we liaise extensively already. We share information between ISO and IEC and CEN-CENELEC and members, so I would never exclude that possibility in future, but in terms of machine readability, we’re still understanding exactly what we can do and what we hope to do.

ANJA: Eventually it will be in the interest of all of us—are common members, but also our organisations—to come up with solutions that are interchangeable, or that can be used in the same process without requiring too much change going from one system to the other or implementing those systems in one national organisation.

What are some of the cool things that are going on right now with SMART standards?

KYLIE: Certain technical committees are very data centric. They’ve got data in a database of some kind, or even an XML file a particular kind. And what they do is they transform that into a document for our production process, and this is something that some are fine doing, but some would prefer that we provide the data as it is as the standard.

Another example is that some of our members have used the XML that we’ve provided to them to create new products and services for their national markets. To that end, they would like to see certain changes or a bit more granularity in the XML so that they can further expand on that.

In terms of machine readability, we have a few pilot projects ongoing at ISO that involve various proposed standards in different formats. Some are scripts, some require a Git-like repository in order to work and in order to be updated.

ANJA: I’m not aware of pilot projects, but I know that the marking up of requirements is something everyone desires. So, we’re curious to see what comes out of the respective working groups in that context and out of the pilot projects that are running.

Regarding SMART standards versus PDF, do you think it’s going to go one way or the other, or is there going to be a hybrid?

KYLIE: Well, allowing for any possibility, what I see happening is a hybrid. PDFs are still so useful and people are so familiar with them. They’re easy to use. I can see us providing PDFs way into the future.

But in terms of machine readability, that doesn’t mean that that’s all we have to offer, right? We have to look at what users are doing with that information and how can we provide it in a format that is more useful for them.

So maybe they want an Excel sheet, or maybe a repository that they can query. Or if it’s tagged requirements in a very granular, very enriched XML file, that’s also a potential option.

So, this is not an absolute prediction of the future, but I see us potentially providing PDF as well as other formats, depending on the standard itself and the user needs for that particular standard.

Are you seeing requirements for capturing more data for the SMART standards, and will this form part of the NISO STS changes that are coming at some time in the future?

ANJA: What the NISO philosophy is, as far as I understand it, is that we see what is required in industry—what are the ways that have proved useful? And then to try and reflect those ways, but not to come up with solutions. So, I think we need to wait for concepts to evolve before we can even think of putting them into NISO STS.

Has there been any consideration given to publishing standards documents primarily in HTML with PDF simply as an alternate format for download? If so, what were your reasons for and against such an approach?

KYLIE: We do publish a couple of standards in HTML as the kind of definitive format. However, those were published as an exception to our production processes and to our directives.

The production process at ISO and IEC is governed by directives, and there hasn’t been very clear provision about alternative formats to a central document format like PDF. So the considerations really need to be more thought out before we decide one way or another on providing formats as a defined part of our production process.

ANJA: At the same time, you do have the Online Browsing Platform, and at IEC we have the online collection, which allows people to use HTML as an alternative format, but it’s not the primary format. That is still PDF in almost all cases, except for these couple of standards in HTML that we also have.

Is your version of record now moving to XML? It still seems to be PDF in some instances.

KYLIE: Certainly for us, PDF is still the reference version. Changing to XML has been floated a number of times in conversations, but I don’t think there’s any firm steps towards that at this moment.

ANJA: That said, obviously the move to an XML-based way of creating standards is one that will open up lots of opportunities and, with that, lots of questions. At some point we may want to revise some of the old habits that we have during standards development, but that’s certainly not up to us to decide.

When it comes to redline, do you add comments about changes to standards in the ISO Online Browsing Platform, or is that something for the future?

ANJA: At IEC we are still totally PDF-based, so what we’re doing now in terms of redlines is all change tracking mechanisms in Word, and then we convert to PDF. So this, for us, it’s clearly future oriented.

KYLIE: At ISO we use we use an automated XML redlines feature for the HTML view of our standards on the OBP, and we also use a Typefi feature to create a specific redlines product that people are very interested in.

Redlines are an interesting question. I think that’s a feature users will want to see for sure in future, I don’t know how we’ll integrate it into the Online Standards Development Program, or if we will, but it’s something to keep in mind.

The OSD platform does allow comments and it tracks changes, but it’s primarily a drafting tool at this stage. Redlines, as I understand it, would be a feature that comes later, it looks at different versions of published standards, definitive additions and versions, as opposed to drafting.

What’s the initial feedback been for contributors working with Fonto? Have they enjoyed the transition? Has it made things easier for folks?

ANJA: Feedback so far has been positive throughout. Obviously we are in an initial phase where we started out with a proof of concept, we had a few pilot working groups working in the in the editor, and the feedback also from our user groups at IEC and the reference group at ISO who we put onto the system.

And we said, “Now have a look, do you think this could work for you in the future?” And putting aside all the obvious little things that we haven’t yet solved and bugs that we then fixed in subsequent releases, people were very convinced by the general approach, the way of working, and we have now moved on to a phase of having some early adopters in the tool.

Feedback is overwhelmingly positive and they see great potential for the future. We’re still working on bug fixing, and we’ll extend all the possibilities in the future, but yes, I think generally we can say that we hope it’s going to be a success.

KYLIE: Yes, I think so. It’s a little bit of a culture change in a way, because the tool is not a WYSIWYG editor, the way Word is. So there is kind of a change management process that has to be implemented when teaching people how to use this.

I think once users get their head around that, you know, “I’m just putting in the content here, I don’t have to care about what it looks like because this organisation will take care of that for me,” then they get on board.

Why did you choose Fonto?

ANJA: Between ISO and IEC, we agreed that we would like to have an online tool that allows for collaboration, and that can allow us to guide authors through the process of writing their standards. So, hiding all of the things that won’t be needed, and highlighting what they need at each point in the process of creating a standard.

We compared different options, and we also looked at the possibilities of doing something in-house.

Fonto proved to be the most mature product, and it seemed easy to configure. And today we can confirm that it had most of the modules that we were looking for readily available out of the box.

I think most of all, seeing the number of experts we need to extend this tool to, what we really needed was something very usable that could be used without a lot of training, that would be intuitive. And I think we see now that this was the right choice, because it is very easy to use, very easy to configure.

How much training would you need to provide for a contributor who was using Fonto for the first time?

ANJA: Well, initially we did extensive training sessions and we recorded things, put them on YouTube, and it turned out that most people just wanted to go into the tool and try things out.

I would say with at least two groups that we have recently onboarded, or that we are onboarding now, they said, “Oh, we don’t want any training. We know we’ve understood the concept of not having to fill it with layout stuff, but just putting in content, let us go and do things on our own.” And they seem to be doing fine; whenever we request feedback, it’s going well.

KYLIE: As Anja said, we do have videos, and we also do have people ready to answer questions when needed.

Do you think people have been more open to new technology during the pandemic because they’ve had to learn how to use things like Zoom and everything else for everyday life?

KYLIE: That’s a good question. Certainly not one that I’ve directly asked anybody if I’m honest, but I could see that being a factor. This pandemic has forced a lot of people to change how they work and the tools that they use, and perhaps that could be a factor in helping them onboard into this more collaborative, digital focused way of working.

What impact has the new system had on the amount of time it takes to produce a standard? Has it caused delays, or maybe even sped things up?

KYLIE: The OSD is still in its infancy, really. We’re still effectively piloting it. So its effect on the overall development time for a standard still remains to be seen.

If online authoring is not a requirement, are there any other tools available to convert Word to XML based on NISO STS?

KYLIE: The Word to XML transformation process is always a tricky one. At ISO, we use a software called eXtyles published by Atypon, formerly Inera; it’s a plug-in for Word that tags your content and creates an XML file out of it. However, there are other products on the market and vendors who do that as well.

ANJA: And vendors who provide the conversion from Word too, which is the way we are going.

Kylie Rodier

Digital Publishing Manager (ISO Central Secretariat) | ISO

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an independent, non-governmental international organisation with a membership of 165 national standards bodies. Through its members, it brings together experts to share knowledge and develop voluntary, consensus-based, market relevant International Standards that support innovation and provide solutions to global challenges.

Kylie Rodier holds a Masters in Publishing and has experience in trade and academic publishing, with particular focus on XML workflows and digitisation. She currently oversees the XML component of ISO/CS’s publishing chain.

Anja Bielfeld

IT Business Analyst | IEC

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a global, not-for-profit membership organisation, whose work underpins quality infrastructure and international trade in electrical and electronic goods. The IEC brings together more than 170 countries and provides a global, neutral and independent standardisation platform to 20,000 experts globally. It administers four Conformity assessment systems, and publishes around 10,000 IEC International Standards.

After an initial career as a teacher, Anja Bielfeld moved on to the field of Technical Documentation, concluding her Master of Science course with a thesis on multilingual content management. She then managed a localisation team for a few years, before joining the IEC in 2010. Starting out as an expert in digital publishing, she later joined the IEC IT team as a Business Analyst and project manager of the conversion of the IEC catalogue of standards to XML. She is now project manager of the Online Standards Development program at the IEC.