Aimer Media is an award-winning app developer working with publishers and content specialists to create useful and sustainable apps. Since 2009, they have developed well over 200 apps, seen app downloads reach the millions and have thousands of people use their apps every day.

In this presentation from the 2018 Typefi User Conference, co-founder and director Adrian Driscoll looks at how introducing apps into your publishing can increase the value of your investment in content development as well as creating new revenue streams and keeping your end users happy.

Transcript

ADRIAN DRISCOLL: My name’s Adrian Driscoll and I’m here as the co-founder and director of an app company called Aimer Media.

I was invited to talk about apps and publishing, and apologies, I didn’t actually manage to come up with a better name than the title of this one, so I will talk about apps and publishing—how, in one particular case, it’s been a very productive relationship.

I’ll do this basically by looking at my own experience, and the experience of Aimer, in trying to make apps work in publishing, working with predominantly book publishers.

So first, I’ll talk a bit about myself and Aimer, and how we came to be developing apps. I’ll then have a look at why we started with—and ultimately why we’ve carried on working with—publishers for app development, and then I want to look at the process that we have for deciding what apps we do and what the considerations are in play when we focus in on an app idea.

About Aimer Media

So, first of all, where did Aimer come from? Well, sorry but I’m going to take a personal detour into my publishing history.

By way of a background initially though, there has been three key technologies in publishing that were specifically significant for me.

I don’t think for the first two there are any arguments that they both profoundly changed publishing. But I’d say that even for most publishers, even if they’re being generous, they’d say that the jury is still out on the final one.

A bit of ancient history. I started publishing in 1989 and I produced my first digital project in 1992. I ran the Philosophy list at Routledge throughout the 1990s, and at the same time I was there, I ended up developing a series of initiatives and products in what was then called electronic publishing.

I did CD-ROMs, I introduced SGML into Routledge, but it was the arrival of the web that I became obsessed with.

I—well I think at some point in here I say—was “actively exploring the possibilities that new technologies are presenting”. And it was, yeah, I was pretty wired. Both for the magazine and on a personal level.

We did all sorts of things, including my authoring this page from 1997, part of our Philosophy Resource Center.

Notice the self-conscious use of the American spelling of ‘centre’, and in my own words there, “meeting the challenge of cyberspace”, because we still used to refer to this space as cyberspace.

I tried hard to do stuff within Routledge, an increasingly corporate Routledge, but ultimately I left Routledge in 1999 to found a company called Semantico.

Some of you may have come across Semantico. For me, bibliographic resources and journals had already started to shift over to the web at this point. And I was convinced that reference works, especially multi-volume ones, would end up on the web.

So, at Semantico, we developed a solution for publishers of large scale reference works who knew that they needed an electronic product but realised that CD-ROMs weren’t the answer.

We built the infrastructure that these products needed. Not just the concept models, user experience, elements of search technologies for delivering that material, but those things that a publisher needed for the product to support a business model for selling to libraries, i.e. getting a high value product to a relatively small number of customers, but controlling access to the large number of end users.

By 2002 we had put 28 volumes of Grove Music, over 200 volumes of Oxford Reference content, and 10 volumes of the Encyclopaedia Philosophy out. It was a very successful period of time.

As you can see, there’s a clue here, that’s Brighton Pier because we were based in Brighton. I lived in Brighton, we stayed in Brighton, that’s why it was a long journey for me here. I’m still in Brighton and I came down the hill to here, so.

But one of the issues was we relied on very big projects. So, anything smaller we soon realised had to be aggregated into something larger. Some other really interesting smaller projects were left high and dry by this, and I found that personally very frustrating.

For lots of reasons, I sold Semantico to my co-founder in 2005, and I started to become a more general digital publishing consultant. I did more reference projects, specialist websites, digitisation of archives, increasingly less academic and more trade publishing, which meant that when the next interesting technology came along, I was better prepared for it.

In May 2006 I was one of the organisers of an STM conference called Book 2.0, and someone had brought along a demo device of what, in that September, became the Sony PRS500 e-reader, which was the first mass market e-reader. One year later, Amazon launched Kindle.

The arrival of e-books changed digital publishing strategy for trade publishing in a way the internet really hadn’t. It really did strike at the heart of their publishing. I found myself advising on e-book production and related issues.

It was pretty clear to me that this was and is still my position on e-books—that they needed to be integrated in with standard book production, processed as quickly as possible, ideally with systems like Typefi, to improve the production process, ideally reduce costs, and where possible, add new but incremental revenues.

But from a product development point of view, there was no opportunity to really add value in e-books. I did work with publishers to try enhanced e-books, but for me they remain, at least, a solution in search of a problem.

Perhaps most significantly, I couldn’t see a challenge there to create a new business around. It wasn’t e-books that I bet for my next venture, it was apps.

My take on apps was that here was a new business model for software—one that supported micropayments and that came complete with a new supply chain, complete with fulfilment, the App Store. The iPhone came out in 2007, the App Store in 2008, and we launched Aimer in 2009.

Since then, we have created a lot of apps, and we have seen those apps downloaded a lot of times. But most importantly, looking at whether apps work in publishing, we’re still in business, we’re still growing, we’re still doing what we set out to do, and finding new opportunities.

We’re still working with most of the publishers we started out with, at least those ones that haven’t been sold, and we’ve got a new office here in Brighton, we’re adding more people just to meet our existing customer demands.

Why choose to work with publishers for app development?

So why does Aimer work with publishers to find apps to publish? Well apart from that, I want to go a bit deeper into why Aimer’s first step was what I thought that apps could bring to publishing.

As soon as Apple launched the App Store, I felt that they were the missing piece of the jigsaw as far as identifying opportunities in the publishers I was talking to.

There was lots of publishing that could never be aggregated together into online products that clearly worked for STM and academic publishing, nor as e-books, which became established as a solution for trade in its purest form, fiction and narrative non-fiction.

There were lots of different sorts of publishing, like some sorts of reference works, illustrated non-fiction, some sectors like children’s and education, religious publishing, travel publishing, and other specialist areas, that it just didn’t really work for.

So I went out and started to talk to the publishers I knew about what they thought about apps. Aimer was set up to create apps for publishers because I thought they needed somebody like us.

Why did we need them? Well, let’s start with the obvious. Publishers have books full of stuff. Lots of thinking has gone into these books. These are actually some of the books that we have turned into apps.

In fact, two of the books on this screen were produced using Typefi—the Berlitz Cruise Ship Guide at the top there, and the Insight Guide to Paris over on the left there.

So why else? Well, not only do they have stuff that they would like to have in a useful form, and they know about the editorial process, but having material in useful forms like EPUBs or XML, sometimes even in a well-set-up content management system, means that we can actually get a hold of what we think apps need.

Even when they don’t have exactly what they want, we can cope with that, with recreating or enhancing the data in a spreadsheet or simply editing a simple dedicated CMS or database. There was somebody willing to make it that way who was competent enough to do so.

One area that we hoped that publishers would be more useful was for sales and marketing. We literally thought that was one of the key things that the publisher was going to bring to the table. But frankly, they really weren’t very good at it, and even in our best cases they’re still not.

It is, clearly from my experience, it’s very hard to get the right sort of attention for apps. It’s an ongoing problem that we have got, that we’ve tried to address with publishers, but it’s not a straightforward thing.

But despite that, we found that through our experiences, three things did really make a difference. What they did do, not necessarily the obvious thing that we were doing, they provided access to brands, unique IP and audiences.

What do I mean by that? Well, some of it’s really obvious. Our publishers allowed us to publish apps which include brands like the Church of England, the UNESCO World Heritage, the Royal Family, the Tate, the R&A. Instant recognition and reach that helped those apps stand out.

In most cases, publishers have original content, but we found that there was a real benefit in having unique or exclusive IP that was recognised as distinct from other comparable materials.

The official publications of the ILO, the official church materials for use by the clergy, the decisions on the rules of golf for the R&A so that they could be used for judging people’s actions on a golf course, the JRCALC Guidelines for the UK Ambulance Service. Known and distinct material that stood out from the noise.

Audiences is another, it’s more interesting, I mean something that’s more than just the people who buy the books that we create the apps from.

When we were able to get support from the Tate, not just Tate Publishing, the C of E, not just Church House Publishing, the publishing unit, or Hymns Ancient and Modern who actually look after Church House Publications, and even the British monarchy, not the Royal Collection Trust publishing unit, we were able to tap into huge loyal and often global followings.

Even with conventional publishing, we would reach larger audiences in the book market. We did a yoga app with Octopus on a book that sold around 20,000 copies, we had downloads of 200,000.

Similarly, the JRCALC Guidelines, the effort of the Ambulance Service, it provides guidelines for every paramedic in the UK. After the success of the original version of the app, they asked to work directly with trusts to supply the app to the members. So it was likely that we were reaching any paramedics willing to use the app, not just merely the ones buying it.

How does Aimer decide which apps to publish?

So how do we decide which apps to publish?

We’ve published a lot of apps; not all of them have worked. We’ve avoided doing apps that we were sure would fail, and we’ve seen other publishers create apps sometimes that worked and sometimes that failed. In fact, they often failed.

So, what do we look for? What sort of apps?

Well, the obvious starting point is what does the publisher want to do? The most obvious thing for them is going back to the books. The publishers come along with their books, they say, “Will this make a good app? Which books do we have that might make a good app?”

Over time this has evolved, and now we’re working on projects where the app might lead and it may or may not even be a book. But for that we ask ourselves, quite seriously, “The question is will we be any good at it? Have we done something before like this? Is it something we believe in?”

We often take a long term stake in these projects by revenue shares or long term support and maintenance agreements, so we think very hard about what’s worked for us, and can we do something that we’ve already done or transfer an idea from one app to a new app project that has different content, that has a different market.

Obviously location is something that people are very familiar with, as a unique feature of apps. It knows where you are, but your device not only knows where it is, it knows when it is.

So from the very beginning, we had apps that opened at the right time, on the right day, on the right part of the day, on the right point in a sequence. Specific content for the 23rd of May, specific content for a certain time according to the church, on the 23rd of May. It’s currently time for evening prayer.

And specific content that applies when you combine the age of your puppy with the part for when you started training your puppy.

Ultimately, can we think of a way in which we really add value? Key to this is the idea that the functionality we enhance the content with is really useful. They value something, in particular combinations—the device, the software, and the content—that becomes the app.

We’re gradually focusing on finding the one or two key things that elevate the content to make something the user would invest their time and money in, and finds a place on their home screen.

One thing that I think is sort of as a side, is that it’s very interesting the way in which people refer to apps that they use a lot or they are loyal to. They do refer to them in a more personal way.

It’s their app, they think of it as their app. They don’t feel the same way about websites. You’re visiting somebody else’s website, you download your apps.

I don’t think it’s an accident and I think it’s something that if we try and make sure that as much as possible we’re increasingly trying to reinforce that feeling.

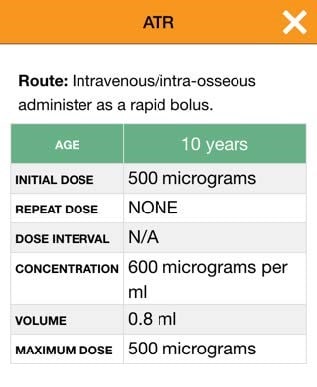

This is a bit of a case study of what I might mean by this. In the full reference version of the UK Ambulance Service Clinical Practice Guidelines, known as JRCALC, there are 584 pages of detailed official guidance for all NHS paramedics.

There is a cut down version of JRCALC with a wipeable cover called the Pocket Book, that condenses the guidelines, pulls out key information, especially the drug dosage tables, into a form that could be carried around by paramedics when they’re out and about.

The app version contains all of the guidelines from the full book, and makes the key information and tables easy to access, like the Pocket Book. In fact, there is a use case where we attempted to try and make it even easier to use.

Literally, I am under a car in the dark, and I want to double check a dosage, I don’t have enough hands to be able to hold the torch as well as turn to the right page in the Pocket Book.

So, we worked on creating a quick route to get to just the information. We had to work with the publisher and the content management team to turn the book tables into data, so that we could then add the ability to filter all drugs by age.

Then we brought dosage tables to the top of the drug’s page on the app as part of a quick reference section so we could create immediate access for the user to a simple, clear summary of the information, as you see on the right there. Simply, the drug, the route, the age, and the dosage.

What was nice about this was this month we had evidence of the success of the approach that we take in a Tweet.

“So impressed with the easily accessible information on my @SECAmbulance iPad last night. Used for a severe asthma attack in a paediatric. More information than the old Pocket Book for severity scoring and quick and clear access to medicine doses!” Thumbs up, #decisionmaking, #jrcalcplusapp.

Well, obviously from my point of view, absolutely delighted that we helped with quick and clear access to an asthma drug for a nine year old who needed help. To be honest it doesn’t really come much more satisfying than that.

By the way, that hashtag #jrcalcplus refers to a version of the guidelines, an app that we’ve got, which integrates the national guidelines with local guidelines. Basically, the trusts have a login, you log in with that, and you see your particular local guidelines integrated with the national guidelines.

We’ve got two trusts in the app, another four in development, and most of the others in discussion.

It’s still early days for apps and publishing

I believe that we really still are in the early days. We’re only just starting to find out how apps can be used in publishing.

We’ve come a long way in our eight and half years. Pepys Diary was our first app. Came out in January 2010, Apple iPhone only. The Apple iPad didn’t come out until April 2010, and it was a single purchase of 1.99.

This was not with a publisher—we developed this to convince a publisher that the idea we had for their daily content would work, and we wanted to show, not tell.

Our latest app is Miller’s Silver Marks. Miller’s is a UK antiques reference product which only went live on Tuesday. This is a cross-platform development initially delivered as iOS for iPhone and iPad and Android, but it will soon be a web app for desktop and laptop use.

It’s with Octopus Publishing, which is part of Hachette, it’s a lifestyle publisher, and we’ve been working with them since 2012.

The app has been designed as a companion to a two-volume encyclopaedia that came out on the same day. The app contains 1,600 silver marks and it’s aimed, at least initially, at a professional market of valuers and auctioneers.

It’s free to download. You need to register to use the app and you can use it free for seven days, then you have the option of a monthly or annual subscription, via in-app subscriptions, and the cost for the year is 125 pounds.

So that’s a big gap. To be honest, I’m not even sure that we actually do just apps anymore. But what we do is definitely app-centric, it’s definitely mobile-led, the whole area is still evolving fast and in different ways.

We want to be part of that for many more years, and we believe that publishers ought to be along for the ride.

Q&A

I’d be very happy to take any questions.

PETER KAHREL: When a publisher brings out an app, for example, Insight Guides, they have a travel guide, and then they bring out the app. Wouldn’t the app bite into the sales of the book?

ADRIAN: It can do. Our experience is generally not.

One of the products that we do is called Reflections for Daily Prayer, it’s a Church of England product.

It’s original content, it comes out, some of the products that are similar come out three or four times a year. They weren’t doing very well with it, so they started doing it as an annual volume.

We’d successfully produced another apps in that area for two other publishers and they asked us to look at that, so we produced that for them.

As a result of that, not only was our app really successful, their Kindle version became much more successful, and their print became more successful. So it actually was quite the opposite, it was a win, win, win.

And it’s not always the case, but it’s not been my experience that cannibalisation is the normal thing.

CHANDI PERERA: Adrian, can you expand a bit more about what makes a successful app and what might lead to failure?

ADRIAN: Obviously I’ve mostly been interested in apps that you charge money for. I’m a publisher by instinct, I find it much easier to work with things that have got a price on them.

But what we’ve found is that, we’ve found it a lot easier to work with organisations that have a mission, because, well, with the pressure on mainstream commercial publishing, particularly I still do work with academic publishers, and the pressure on them is immense. So it’s very difficult, in some cases, for them to see beyond the short term.

And so it’s certainly been the case that if you can have a more longer term view, a more committed view to say, “So we’re doing this for more than just simply that thing,” then you actually are much more likely to be successful.

If you’re looking for a short term win, if you’re judging it by its initial fee, certainly in an area where there’s not a genuine mass market—most publishing, even in trade publishing houses, most of their books are actually really only going off to a relatively small part of the market.

So it’s not, you know, in an app store where you’ve got games and social media, where you are literally talking about potentially reaching significant proportions of the planet, and our most successful apps, we’re still only talking about tens of thousands and in some cases hundreds of thousands.

When you look at the numbers that are downloaded for some of these, they are talking about millions. So you have to be realistic about what is possible.

And then the other thing that I was pretty clear of from the beginning was that I didn’t want to just do one or two apps. I felt that it was certainly to reflect the publishers, we had to do lots of apps, and certainly working out how to do that.

A lot of publishers fell foul of Apple’s review things that stopped you basically just doing something like a book, like a series where you could just do lots of similar, similar apps. They just didn’t like that and they still don’t like that, and so you have to be more creative.

And I don’t think they’re wrong. I mean ironically, I don’t think they are wrong, because as we have found, it’s very difficult to basically get in something that’s effectively a timing of a window for the App Store to try and distinguish yourself.

And it’s clearly something that you have to work on, but it’s clear that, for mine, if you have a strategy for producing an app, from our point of view, we take it on if we feel the publisher has a strategy that we can both agree on, and it really isn’t short term, it has to be longer term.

I think of it very much like series publishing. You wouldn’t judge a book on the first. If you commit to a series, you don’t—unless it’s catastrophically gone wrong—you don’t can it after the first book. So you’ve got to think about it that way.

Also, it is ironic. I used to have things where they’d say, “Are we looking for a return on investment within six months or a year?” At the same time, they’re taking on academic journals, which is pushed out to eight years plus before they make a return.

So it’s something which is clearly problematic, maybe in decline, could be under threat in a way that cannibalisation isn’t, from OA or something, but won’t take a punt on something that might, that clearly had actually—it may be in our experience—it starts off small but it does grow. You just have to be patient.

LAURENT GALICHET: When you say take a punt, how much was the average, what was the average cost?

ADRIAN: We were really, really competitive at the beginning, I mean, we were desperate to try and prove that it was worth doing this, which is why we had a lot of revenue shares.

One thing I think is really interesting, we did take on a couple of projects where the publisher didn’t put up any money, but we did the share. That didn’t work.

So what we found was actually, the optimum was they had to put money in, otherwise they didn’t care. But they didn’t want to put that much money in, so they were quite happy to give away quite a lot of the share of it.

So, in some cases, some of our most successful projects are because the publisher was pretty tight at the beginning and let us take on some more of the risk. We took on more of the risk and it’s been a long term benefit to us.

Now we have more serious conversations with people before we get going, but we still think we’re relatively competitive.

And I think that certainly, I mean, one of the complications is because increasingly we’re talking about cross platform, and there is a cost in delivering properly for each of the platforms that you are delivering to, but it’s still not a million miles of saying that it’s anywhere between 20,000 and 50,000 pounds to do a proper project.

That’s not just one app. That’s usually a proper project. It could be one app, because you could be refocusing into just specifically making the app, but inside that app is a lot more than just maybe a sequence of apps or something like that.

We’ve got 21 apps we’ve produced for kids’ primary school apps. That’s no different in many ways than the one app we’ve got for the JRCALC class or some of the other projects we’ve got which embed more inside one. It’s multiple products inside a single container.

And obviously that’s pretty confusing when you compare it to something like books or even to some pre-journal publishing where there’s a sort of similarity. Fluidity of the business models, that’s quite hard.

JASON MITCHELL: Hi. How do you prefer to get the data for the apps?

ADRIAN: Oh, prefer? That’s a good question. What we’d really like is really well-structured XML with lots of semantic enrichment that is predictable and reliable, but that doesn’t really happen very often.

We have done that. I was talking the other day about Wiley, we did a project with Wiley, we did a haematology app. We were really looking forward to doing more of it, but they, Apple, came along and promised the world with their iBook textbook stuff, which of course didn’t go anywhere, and then they shifted the whole content, they off-shored it all, and so there wasn’t enough in it.

If it works, it doesn’t matter. So, for example, in quite a few cases, we’re taking EPUBs, and we’re putting them into somewhere so that they can be reviewed, and then enhanced with additional data.

So as long as we’re doing that, we’d like that to be in their content, part of their content pipeline, so that we get that with all that information in.

But we have adapted to basically meet the publishers halfway, and say okay, if we give you the tools, often so that we can get on with something else, rather than effectively, in some cases, charge them for making their data better, I’d rather they made their data better, and then we got the app.

CLIVE BULLEN: Yeah, hi there. I’m interested in that we’ve got lots of questions, multiple choice questions, they’re just A, B, C, D or multiple response, you choose two out of four or whatever, and they’re within Typefi.

What I’m interested in is have you got, or are you aware of any other apps, that would take that sort of question, put it into something which is in an app, and then the student can just click on the A, if they think that’s the right answer, and so on?

ADRIAN: Oh yeah, I can you show you two or three that we’ve got, and it’s not, if it’s in a reasonable form, which I suspect it is, that really would be, I mean that’s the sort of thing that I would want.

Actually, the haematology project we did was called Clinical Cases Uncovered, and that’s what was beautiful about what we got there, it was the full text of the book, and it was the quiz base inside it, and it was the extra material.

So we were able to produce something that really was a super set of the data that they had available, that they’d split out to different things.

And that is ultimately, in some cases, we’re enhancing the data considerably for the app, so for example, we’re increasingly putting audio in, and we’re also, in some cases, we’re entering APIs in it.

The last, one of the daily apps I did, the Live Lent app, that contains audio as well as the text that’s prepared for that material, and it has it connected to an API that allows you to work out where your nearest church is.

And that’s definitely one of the things that we are looking at, which is that ability to make it very useful by putting in just what that person who’s using it would find useful at that moment, and then gradually working out how you might increasingly, increasingly we started off with the concept that each of the apps has a dashboard, and that dashboard ultimately becomes trained to the user.

CHANDI PERERA: Is there a specific type of content or segment that works well in apps and ones that don’t?

ADRIAN: Anything highly structured works really well in apps, I mean that’s one of the things, reference works really, really well in apps.

We did lots of things like that, certainly things that are where there is implicit in the content model, is some sort of action, so when it can be a tool, when it’s used for something, things like checklists or looking stuff up.

And some of the apps we’re doing, we’re extending some of the apps by putting in things that allow somebody to go through a flow chart model to do something, so quizzes or quasi-quiz-like material, things that the app does really, really well, so it can calculate, it knows about time and place, anything like that, that’s the stuff that really does well.

Certainly, one of the things I think is interesting about my point about audiences, is that when you come in from the publishing perspective, certainly with mainstream trade publishing, there is an assumption that everybody important in the world is people that read books.

But I think if you look at the size of markets for game software and actually the number of—I had some slides on the number of apps in the world—and the number of downloads, it is ludicrous, and then when you compare it to publishing, you realise that despite the vast variety in that area of publishing, this is already getting pretty big.

Games overtook the whole of all the other industries, of the entertainment industries, all put together last year.

So it’s like we do come from a rather narrow, bubble point of view, and so trying to tap in to some of those aspects, where actually there are people that will use what you provide them, and so, certainly the case at mission-based organisations, they don’t really care whether or not somebody reads a book or uses an app.

If it’s achieving the goal that they set out to make, they’re quite happy, and that is one of the things that we find quite refreshing when we’re in that situation that there is no conversation about, well, because we do certainly get a lot of resistance internally, in more mainstream publishing houses, where they really don’t like electronic products or digital.

So there’s a lot of conscious unconscious passive resistance, which we have to work quite hard to overcome, to be frank.

Adrian Driscoll

Co-founder and Director | Aimer Media

Adrian Driscoll is the co-founder and director of the app publisher, Aimer Media. Aimer is an award-winning app developer working with publishers and content specialists to create useful and sustainable apps. Since 2009, they have developed well over 200 apps, seen app downloads reach the millions and have thousands of people use their apps every day.

Adrian was for many years the philosophy publisher for Routledge before founding the digital publishing services company Semantico in 1999. After his sale of the latter, he has provided digital publishing consultancy for a wide range of publishers with Caxtonia.